“Vision is always a question of the power to see—and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”

Donna Haraway (1988)

When Futures Don’t Resonate

This article began with a conversation with a friend, a lecturer in interaction design1. Though we both admire Speculative Design in principle, we found ourselves facing a nagging question: why do many speculative projects feel like they missed the mark? Why do even clever, provocative, and visually striking projects sometimes fail to resonate?

One can certainly argue that this distance is intentional. Speculative design embraces “radical thinking” to break away from the constraints of the present. Yet if one of its aims is to spark reflection, conversation, and critique, shouldn’t it connect in a meaningful way to how people understand their lives in the present?

So, what can we do better for speculative design to resonate? And what gets in the way?

One possibility is that speculative design2 leaps into the future by treating the present as a sanitised and self-evident reality rather than examining it as a complex, contested terrain. In doing so, it decontextualises itself, flattens time, and eventually detaches itself from the lived experience it claims to reflect or challenge. If speculative design is to truly give a glimpse of the futures that resonate with specific groups of people, it needs to treat lived experiences not as a narrative device, but as a situated, embodied, and historically conditioned reality.

To do that, speculative design needs to look carefully at the ordinary. At the objects, routines, and relations that make up the present as a dense site of worldmaking. This is where anthropologist Joseph Dumit’s (2014) “Implosion Project” becomes valuable. Inspired by Donna Haraway’s concept of situated knowledge (1988), and in dialogue with Gilles Deleuze’s (1989) critique of the clichés, Dumit offers a way to trace the complexity of the present by unpacking the seemingly mundane.

Speculative Design and the Problem of Time

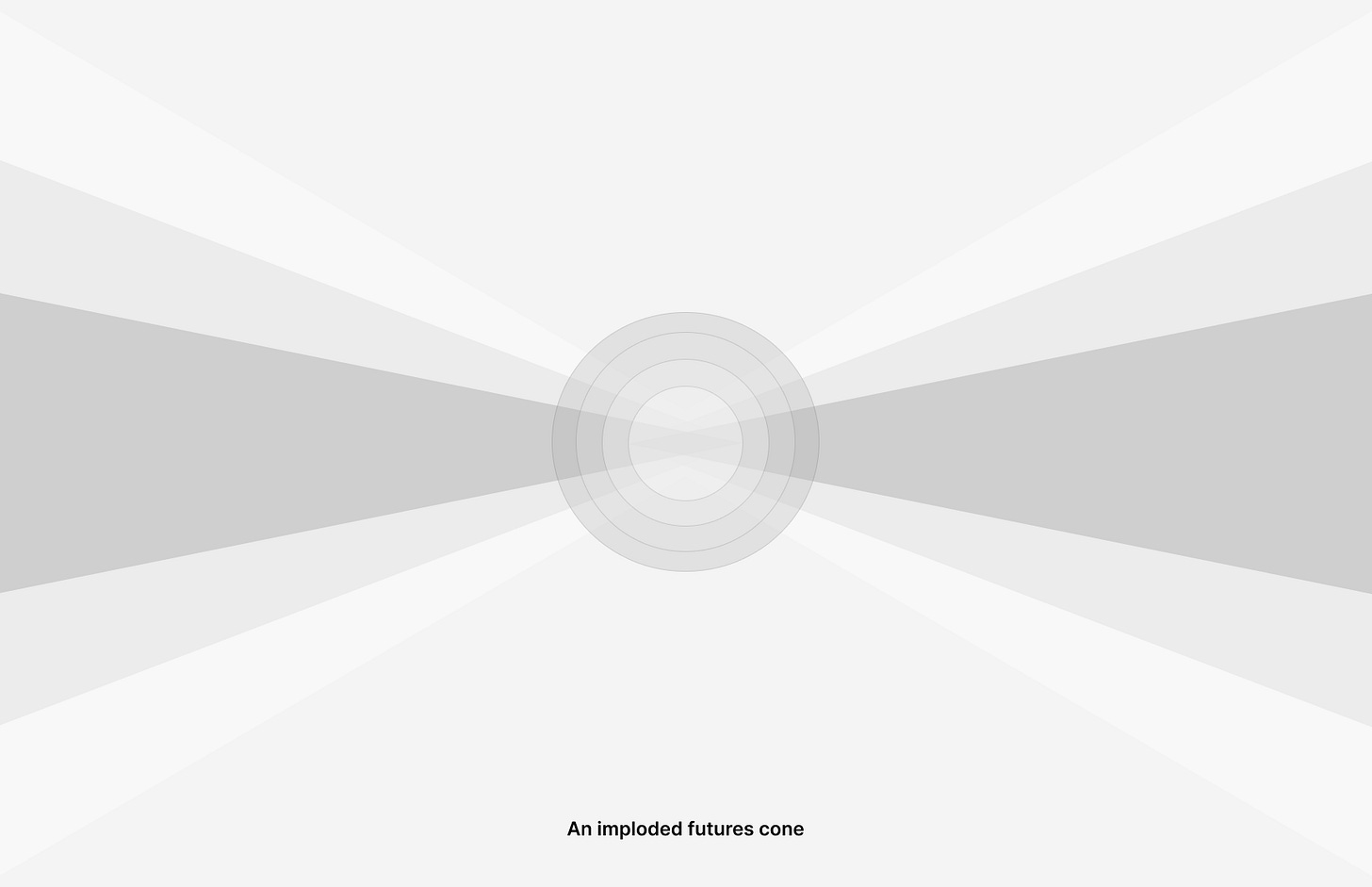

To understand why speculative design sometimes struggles to resonate, I started by looking at how it approaches time. A core methodological imposition of speculative design is in its temporal orientation. The field is structured around the idea of designing (for) possible, plausible, probably, and preferable futures. Frameworks like the “futures cone” visualise these forward looking projections from the now. While it is useful for mapping multiplicity, it implies a fixed present from which futures unfold.

But the present is not neutral. It is not evenly distributed, nor clearly defined. It is shaped by histories of violence, resistance, labour, displacement, and other negotiations. When speculative design treats the present as a clean slate, it bypasses the very systems and conditions it might otherwise critique. This is particularly problematic when designing for “lived experiences” which is the place where such negotiation takes place and becomes embodied.

The past in futures thinking is important. It is the foundation that differentiates speculative design from being a discipline of engaged critique from the one of escapism. Our perceptions are shaped by partial, layered, and historically situated processes. Speculative design that ignores this risks producing the futures visions that are imaginative, but unrelatable, and, ultimately, unaccountable.

Imploding the Ordinary

Dumit’s implosion method offers a powerful approach to engage deeply with the present and its histories. Developed as a teaching tool influenced by Haraway’s concept of material-semiotic objects, the “Implosion Project” asks students to select an ordinary object (like a pill, a t-shirt, or a coffee) and unpack it across multiple dimensions (see image below). The goal is not to merely analyse, but to understand how the world is inside an object, and how the object itself is part of wider world systems.

To implode is to treat an object as a dense meshwork of histories and relations. Objects allow us to trace systems of production, categorisation, conflicts, and imagination. Dumit’s implosion method involves three twists:

1) the knowledge map (what you think you know),

2) the ignorance map (what you do not know), and

3) archives, experts, counter-memory (who structures and holds knowledges).

These exercises train us to stay in complexity. They are supposed to be messy and overwhelming. Through implosion, “you can start to see the contours of knowledge and attention that maybe help explain how you came to know and not know.” (Dumit 2014, 357) In other words, implosion reveals the conditions of perception and the structures of meaning that shape what we see, ignore, or are taught not to ask.

In speculative design, the speculation often involves projecting possibilities by asking “what if?” Implosion helps us begin thinking about the futures through the present by asking “what is already here that we fail to see?” It compliments the speculative process by setting the entangled present as a precondition for building the necessary complexity and accountability of the speculation. It grounds the practice that otherwise would float free from the systems it aims to critique.

Lived Experiences, Situated Speculation

Speculative designers frequently aim to build upon “lived experiences” in order to help audiences imagine themselves in another world. But what makes an experience lived is not just presence or interactivity, but the conditions that make it intelligible, meaningful, and affective. These include language, memories, bodies, infrastructures, and shared histories.

With the concept of “situated knowledge”, Haraway argues that all seeing, thinking, and knowing is partial in a sense that we never look at the world from nowhere, and that somewhere matters. The Implosion Project offers ways that we can learn about the world in an object, and in doing that recognise our own position in relation to it. Implosion turns our attention to positionality and implication.

This logic can be applied to futures work. The “lived experience” of an imploded future must be constructed through specificity. Who is living this future? How did they arrive here? What history do they carry? What body and infrastructures enable their perception? Without these questions, speculative design risks simulating experience without accounting for the complex structures that produce and limit it.

From Distant Futures to Depth of the Present

Speculative design often emphasises alternative futures. But when it begins by projecting forward without attending the layered complexity of the present, it risks producing designs that feel detached and unaccountable. The issue lies with how the present is often treated as a self-evident platform, and not a contested complex with histories. When this happens, speculative narratives lose resonance, especially with the very people they aim to address.

The method of implosion by Joseph Dimit offers a compelling set of exercises to counter this orientation. Rather than starting from imagined futures, implosion begins with the ordinary and how this constitutes the present. It brings the mundane to the focus to show how deeply they are embeded in systems of power and meaning. Implosion insists on complexity and partiality as conditions for knowing.

If speculative design is to build richer, more grounded narratives of the futures, it must turn toward what it often passes over. It is in these “thickening” (Geertz 1973) exercises that we get a true glimpse of the unknown rooted in the overlooked dimensions of the present. They reveal alternative perspectives and histories, as well as the structural and systemic violences that shape the present condition. Rather than imagining the futures from a distant or generalised present, I believe it is in these margins and edges of depth of what is already here that a meaningful speculative work can begin. A good speculative narrative does not escape these tensions but emerges from them. It is capable of speaking to the futures it hopes to shape.

References:

Deleuze, G., 1989. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by H. Tomlinson and R. Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dumit, J., 2014. Writing the implosion: Teaching the world one thing at a time. Cultural Anthropology, 29(2), pp.344–362.

Geertz, C., 1973. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

Haraway, D.J., 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp.575–599.

Thanks to Kai Wanschura for a thought-provoking conversation and an encouragement to look deeper which eventually led to this article.

Important to note here that speculative design is not a singular or unified practice. It encompasses a wide range of methods and epistemologies from Indigenous futurisms to critical fabulations and participatory scenario-building. My critique here focuses on the dominant strain of speculative design that has been popularised through exhibitions and design fiction toolkits. This version often emphasises conceptual provocation and aesthetic estrangement, while underplaying contexts, material histories, and lived experiences.